Sermon - Jun 26, 2021 A risk of faith

A risk of faith

There’s nothing like a fresh look at something to get things jumping. A brief vacation – disconnected from the technology that has been connecting us; a couple of nights sleeping among the trees; a mental reset that brings fresh thoughts to bear on old concerns – this has helped (I hope) give me a fresh look at things.

Of course, some things resist the benefits of such refreshment. The continuing revelation of our hateful treatment of First Nations defies description even as it demands action. The false optimism and political posturing that surrounds public health issues is no easier to understand today than it was prior to my time away. Some problems get more urgent. Some challenges seem designed to wear us down.

Twelve years is a long time. Lots of chances for second opinions – for fresh perspectives. Twelve years can turn a reluctant six-year-old into a confident High School graduate. Twelve years feels like a lifetime when you are young…or when you are struggling…or when you are sick.

Twelve years of mis-diagnosis. Twelve years of social rejection (bleeding women are not welcome on the social calendar in the ancient world.) Twelve years of being told to move on – to get over it – to get saved – to get lost. This woman’s hopes were so far dashed that her last, best hope is to let her hand graze the garment of this travelling mystery man.

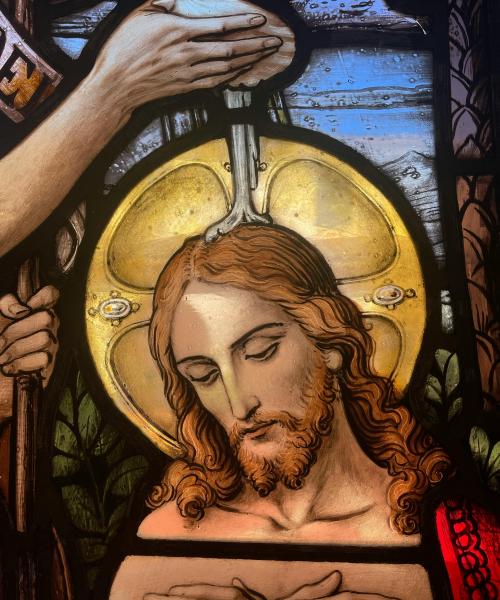

She’s in the crowd, so it’s likely she has heard the stories – perhaps, since she’s close enough to touch his robe, she heard Jairus’ plea to come and heal his ailing daughter…and she knows Jesus has acknowledged the request – sees Jesus making his way with Jairus… maybe that’s why she takes what Peterson translates as a risk of faith.

+++++++

The Message – the translation of Scripture that I’m using today throughout the service – is where I go for a ‘fresh look’ at the Biblical text. The late Eugene Peterson – pastor, poet, educator and author – wanted to bring freshness to these ancient stories when he embarked on this project. From his first efforts, published in 1993, until the release of the entire translation in 2002, it was clear that this was a labour of love; but it was also a risk of faith.

For it is a risk to reimagine and rearticulate the words of the Hebrew prophets and poets; a risk to ask people to hear Jesus’ words arranged in modern idiom. It is a risk to ask people to examine long held assumptions in light of new discoveries.

The crowds that the gospels describe – those eager, desperate, curious crowds that gathered wherever Jesus was – knew about risks of faith. Eager to believe; desperate for some sliver of hope; fuelled by their curiosity about this wandering, welcoming man of God, they clamoured and cried out – wondering if here, finally was the lifeline that God had promised. The risk of faith is taken the moment you decide that you have heard God’s voice; that you have encountered a Holy presence.

++++++++++++++

Twelve years is a long time, but for some, that’s how long it takes before they are ready to take a risk.

The crowd on that day was anticipating something special. Jairus has come begging for help, and Jesus is making his way to Jairus’ home. The crowd imagines that witnessing a miracle – just being there - is risk enough. The limit of their risk is that they hope only to see something. But one poor, suffering person wants more – just as Jairus wants more. Their risk is personal – their faith demands a result.

The disciples were right to be sceptical. “What are you talking about? With this crowd pushing and jostling you, you’re asking, ‘Who touched me?’ Dozens have touched you!” The ‘power’ that flowed from Jesus – this rush of virtuous energy that stops the flow of blood – isn’t like a divine static charge. Dozens have jostled Jesus, to no effect. But this one takes a risk. This one wants something - expects something. Indeed, her faith demands something.

That force of will – the embodied belief (pistis) that this woman carries like a talisman – draws healing from Jesus like a magnet. The woman knows instantly that she is well. Jesus knows instantly that something has changed. The risk of faith has divine consequences, and Jesus honours her risk…and pronounces his blessing.

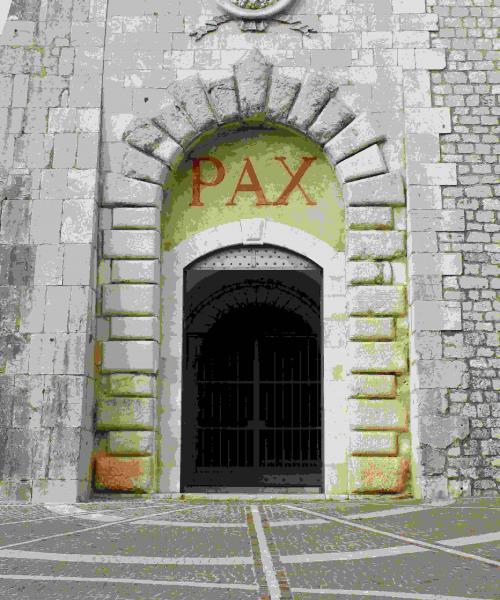

It seems to me that being the church demands that we take a risk of faith. Not just to establish a congregation, or build a sanctuary. To ‘be the church’ requires that we constantly expect something from our faith. Too often the church acts as a static thing – a repository for hope rather than a well-spring of result. We talk about ‘active faith,’ which is a helpful image, but faith is a noun – something given by God that works only when we wield it. Faith is a tool, not just an attitude. Faith activates things in us and around us. Faith helps us boldly attempt the impossible; blithely expect the improbable – all while accepting the risks inherent in the demand for healing, or recognition, or justice.

Faith is thus a two-edged sword, ready to cut both ways. Faith in an institution – in a government policy – in prejudicial thinking – in bigotry; such faith has driven people (within and beyond the church) to generations of hateful, hurtful behaviour toward those who were deemed expendable, unworthy or not recognized as fully human. Clothed in the mantle of Christian faith, those behaviours became accepted practices – practices which we need to recognize as sinful. Behaviours for which we need forgiveness…not just God’s forgiveness (of which we are conveniently assured!) but the forgiveness of those whom we have harmed.

The wounded are everywhere, having waited twelve times twelve years to be noticed – to be understood – to be acknowledged. The various apologies and pledges of repentance offered by the church down the years are but a start. The wounded have reached their last, best hope. Their grief has pushed them to the edge, and the affirmation of the horrors- horrors we refuse to believe possible - have given the wounded courage to demand action. I pray that we are finally being jostled into awareness. The power of compassion is being unleashed, and we must allow that power to do its work.

It will be hard work, because it means the church has some unlearning to do. Our history – no matter how earnestly we argue our good intentions – accuses us. The invisible now stands in plain view, and Jesus bids us open our eyes and see…see the consequences of our actions, and see the new paths open to us – paths of common purpose, common learning, reconciliation and wholeness for all.

St. John's

St. John's