Sermon - Nov 21, 2021 Delusions-and-grandeur

Delusions-and-grandeur

Kings and kingdoms throughout history have followed a certain pattern: a Powerful ruler seizes power through conflict and holds that power by instilling fear, controlling wealth, and convincing the masses that they rule by divine right. Sure, there were some who ruled with compassion, and certainly our most familiar monarchy – the ‘House of Windsor’ – has shed most of the worst of its medieval bad habits. But in the vast span of history considered by Scripture, the notion of kings and kingdoms was all they had, and that notion was shrouded in fearful mystery.

Even the Hebrew people, generations away from their deliverance from Egypt, and unsure of their status among other nations, plead with God for a king. The argument boils down to “everyone else has a king…” and God grants the request grudgingly…and soon, Israel is like all the other nations; prone to attack – subject to the imperfect judgement of a long line of human sovereigns – and ultimately, overpowered by neighbouring kingdoms whose charter doesn’t include compassion or honour.

So, when prophets like Daniel are gripped by visions of deliverance, these visions look to recreate the kingdom model and search for a more perfect king. And this imagery of an Ancient One perched high on a throne – smoke, fire and ornamental brilliance all around; worshipful attendants as far as the eye could see; judgement offered and punishment handed out – This is what a just and perfect kingdom looks like when the only other model is confusing rule at the hands of a changeable, human despot.

In Daniel’s vision, it’s orderly, it’s eternal, and it is given into the hands of one ‘Like a human being, coming with the clouds of heaven,’ who is given dominion over everything. Sound familiar?

What humans want is a perfect version of whatever is currently in front of them. And while political systems have changes significantly in the last two thousand years, the image of perfection that the church has been chasing is still rooted in these visions and images of ‘eternal kingdoms ruled by a sovereign being.’ It has seriously affected our image and understanding of God, and, by extension, our image and understanding of Jesus.

According to the gospel of Mark, the disciples were concerned about the problems that they would face during a transition between Roman rule and the emerging ‘kingdom of God’ that Jesus was describing. And Jesus doesn’t dismiss the notion that some suffering is coming their way. It will come suddenly and without warning – and so far, this satisfies the disciple’s desire for change. Out with the bad and in with the good, right? All will be well, right? Right?

“And if anyone says to you at that time, “Look! Here is the Messiah!” or “Look! There he is!”—do not believe it. False messiahs and false prophets will appear and produce signs and omens, to lead astray, if possible, the elect. But be alert; I have already told you everything.”

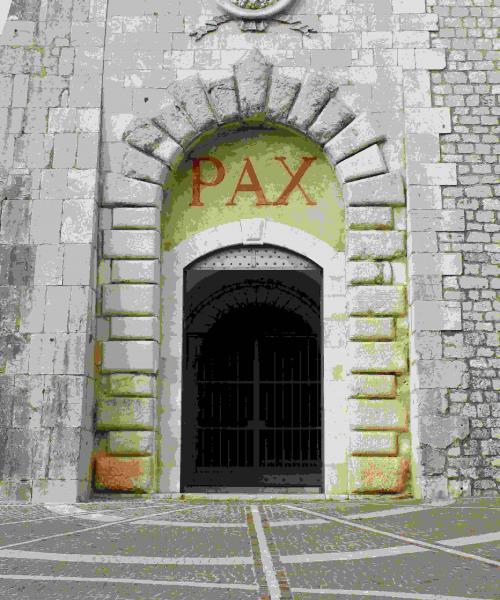

Jesus’ warning suggests that the kingdom we wait for – the kingdom of promise and peace – the eternal excellence that the faithful long for will NOT follow the well-worn patterns of kings and kingdoms of old.

Jesus even quotes Daniel – offers the image of one ‘coming in the clouds’ – as an appeal to the traditional hope of God’s people (that the old order will be swept out with the force like a natural disaster – a sudden, cosmic thing) but lest we be fooled, Jesus also reminds us that he has ‘already told us everything.’

And what (at this point in Mark’s gospel) has he told us?

He has told us which is the greatest commandment. He has cleansed the temple, scouring the religious institution (at least symbolically) of the corruption and rot that had overtaken it. He has welcomed children and praised the widow who gave everything she had. He has raised up the lowly and ridiculed the powerful and tried, by word and deed, to demonstrate the values and principles by which God would rule. No ornate throne rooms – that’s the stuff of prophets and the dream of the desperately oppressed. No trumpets or elaborate parades – his own arrival to the capital is a pantomime parade at best. The kingdom heralded by Jesus sneaks in on sock feet and is known in the little things – the empowerment of the poor and the shared humanity of those who can no longer be called ‘subjects.’

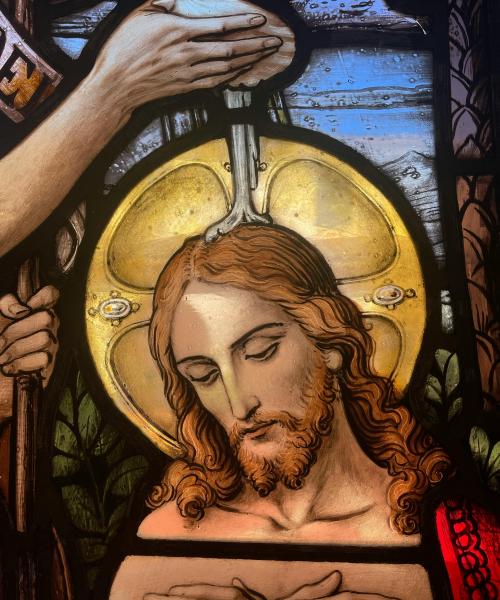

The ‘kingdom’ of God is more like a divine co-op of compassion and grace, each member helping the other until needs are fulfilled and wants disappear. The kingdom of God is a glorious, unimaginable thing, and the personification of that kingdom is the one we call king. Humble, wise, gentle but no pushover. Jesus of Nazareth – teacher, healer, and sovereign.

It’s not wrong to want to celebrate him robed and crowned – but if we imagine that’s all there is – if that is the only way to consider God’s reign on earth – then we are doomed to repeat the mistakes that even the disciples made:

To imagine that the king would rule in our favour against our enemies.

To consider that God only wants to replace an oppressive regime with some sort of divine oppression.

To believe that the grandeur of royal rule must mean that someone will suffer – no matter how satisfying it might be to hope for the suffering of our enemies.

These are the unfortunate delusions granted us by the language of kings and kingdoms, and Jesus promises better. God offers more.

Soon we begin our preparations to welcome the king – born, not in a palace, but a barn. Born to people whose family tree stretches back to the great kings of Israel, but which also includes foreigners, and people of ‘ill-repute.’ We will sing songs of hope, and listen expectantly to the promises of angels. But we ought not forget that this king of ours offers so much more than just the status quo. He does, in fact, promise to turn the world upside down, and introduce us to such a ‘kingdom’ as the world has never imagined.

Soon may it be so.

St. John's

St. John's