Sermon - Mar 27, 2022 Fathers and free lunches

Fathers and free lunches

So, this is a parable about relationships. Parents and children – the lost and found – the worried and welcoming. It a very relatable story. This parable resonates because it covers emotions that we’re very familiar with: expectation and anger and anxiety and guilt…just to mention a few. This parable resonates because the entanglements we have with family members – no matter what our family might look like – include jealousy, longing, comparison, and resentment…just to name a few. The mechanics of the relationships depicted in this parable are wonderfully, maddeningly human. The lessons on offer are universal and divine.

And of course these lessons can be used for other kinds of relationships – that’s how parables work. It is worth considering how this parable speaks to the systems that we’ve developed to manage our relationships down the centuries. Nations could learn a thing or two about their expansionist, colonial or otherwise destructive tendencies. Never forgetting that there is no national or institutional equivalent of the father figure – Let’s be clear on that; in terms of my evaluation/interpretation of this parable, ‘father’ = God/YHWH/haShem/the great I am - the Divine Complexity.

And what does the father want, but to know where the children are – to know that they are safe and thriving and living to their potential.

IF that means doling out the inheritance ahead of time, so that wild oats might be sown and the world explored, so be it. No judgement – no conditions – no expectations of ‘return on investment.’ Take and go; be well. That’s all.

If that means keeping the home fires burning and cooperating on the operation of the home place with the child who won’t stray, and can’t imagine any good beyond their own ridiculous work ethic – fine; so be it. Thanks for all you do.

And if this family dynamic is applied to the church – to an institution that has seen its share of division and has been diminished by indifference – what could we learn, I wonder?

In the PCC, we regularly go ‘round and ‘round over important issues of the day. Positions are taken and sides are chosen and each one imagines that the other is the ‘wasteful, younger child.’ Impassioned pleas concerning the ‘sanctity of our tradition,’ or the ‘integrity of our witness’ are offered. In recent years we have even heard of some who want to ‘take their inheritance and go.’

These are challenging, often hurtful discussions, and it would be easy (it has been easy!) to pose as the dutiful, elder brother; to claim some imaginary moral high ground. But when we do this, we are forgetting that there is a third character in this parable – the most important character. And Father knows best.

What does it mean for a church – on the verge of tearing itself apart – to know there is one who loves both sides equally well? What does it do to our arguments to learn that the authority in the centre of the controversy offers judgement on neither the one who leaves nor the one who stays? What does it mean when, at the height of the elder brother’s indignant rant, the one who has the authority to judge – to decide – to discipline – offers only gentle words of reconciliation?

This is not a parable that ends with family unity – not as we imagine it. The brothers don’t kiss and make up – perhaps their relationship was always troubled. What we get in the end is a lesson in diversity from the head of the household. The father says to the younger “welcome home,’ without a trace of irony or anger, and to the elder he says ‘your home is still here,’ without resentment or frustration.

In this parable, the father is happy when the children are ‘found’ – when they are true to their nature; the adventurous, jet-lagged younger, and the hard-working, stay-at-home elder. After they have made their choices and are in the process of learning their lessons, they acknowledge where their identity comes from. Oddly, it’s never clear that the sons are happy; but they are home, and that counts for something.

And what does ‘home’ look like? What does it mean to be found?

In this parable, to be ‘found’ – to be ‘home’ – is to acknowledge your father; to recognize the gifts that come with being part of the family. To begin to understand that while some waste those gifts and some hoard them, all are equally loved.

This parable doesn’t work if it’s only about one brother. And if it was just the story of two feuding siblings, it offers no good news. This parable endures because God is in the midst of it; the father figure who acts like no father we’ve ever known.

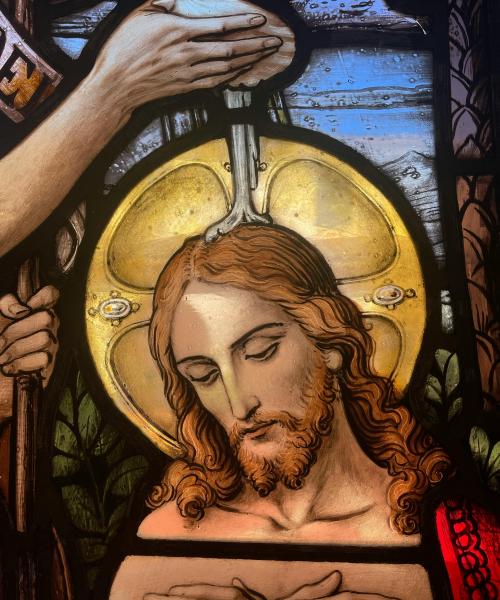

For here is a father who leaves the children to their own devices, and loves them in their lovelessness; who welcomes both the steadfast and the screw-up; whose door is always open, and whose love knows no limits.

Here Jesus tells us (again) what the kingdom of God is like. And whether we imagine ourselves the elder or the younger, we must remember that while we can find excitement and adventure – or we can cultivate contentment and hold on to the familiar – but without the father’s love there is no resolution, no redemption, no hope of peace. The good news is found in this; God waits, not for our success, that we might boast; nor for our failure, that we might repent. God waits for us to remember that we are part of a large, diverse, often difficult family, all of whom are looked for and loved in equal measure.

St. John's

St. John's