Sermon - Oct 24, 2021 Fear the Lord

Fear the Lord

Not many of us enjoy being afraid. Oh, we don’t mind the things that make us jump (and later, laugh self-consciously) – movies, haunted house rides at the fair, the neighbours motion-activated Halloween decorations – but that’s not real fear, is it. And you know the difference. One gives you that tingling feeling – an exhilarating feeling. The other keeps you up nights, affects your appetite, and lives in the darker corners of your brain.

Fear is a primal and real motivator where our behaviour is concerned. I’m talking about fear of injury – fear of retaliation – fear of loss (of anything) – fear of death. All these fears can, in their own way, protect our interests. They also can significantly guide our behaviour.

I mention this because I wonder, after reading Psalm 34, if we could talk about this phrase – the ‘fear of the LORD…’ What behaviour is guided by a fear of the Lord? Whose interests are protected if the faithful and beloved children of God are REQUIRED to be fearful of the Lord of love and life?

This is not the only place in Scripture that this phrase shows up. It is a common enough theme – one that has found it way into modern understanding, common and well-loved hymns, and it has always troubled me.

Sure, if you imagine that God is rooted in vengeance and loves nothing more than watching servants grovel, then ‘fear the Lord’ is reasonable and prudent relationship advice. But for those who understand God as much more than ‘bringer of justice,’ the notion of ‘the fear of the Lord’ needs some unpacking.

And I’ll start where I always start; with the words. And Hebrew has several words that have been translated into English down the years as ‘FEAR.’ One of those is phachad – used to describe the primal, let’s-make-good-life-decisions kind of fear. Phachad is commonly translated as fear, great dread, terror…you know – ‘be afraid – be very afraid.’ But that is NOT the word that is used in the ‘Fear of the Lord’ passages that fill our memories. That Hebrew word is yireh. Yireh at Adonai -fear that is not terror – but awesome reverence – great adoration – or in Eugene Peterson’s translation (of Psalm 34) worship.

The sense of fear that this word holds is the feeling of nervous uncertainty that fills you when you are in the presence of someone powerful, or something extravagant. The fear that overcame my sister and I when we visited our nana at the house she was minding, and we were confronted by the formal sitting room – which was OUT OF BOUNDS! The feeling conveyed by the word yireh can range from insecurity, to personal insignificance (by comparison) to genuine astonishment that there could be such a marvelous thing in the universe (this was our reaction to the formal sitting room.) these are emotions that alter behaviour and cause us to ‘protect our interests’ but it seems to me that they fall short of deep, primal, truly terrifying fear.

But here’s the thing. If you are translating an ancient text on behalf of the monarch (in order to produce the ‘King James Bible’, or if you are expounding on Scripture (that the general population can’t read) on behalf of the church, and you want to ensure that people understand the gravity of the rules and life choices that you are asking them to adopt as ‘people of faith’ – and you have a choice between ‘awe’ and ‘fear’ when translating a word…you use the word that keeps the people in line.

The problem with the bible – and the problem with the way the church has typically (traditionally) used the bible – is that is has been translated and interpreted in ways designed to establish and maintain an earthly power structure. Sure, God is in control, but those who did the translating (especially in the case of the King James bible) and those who have the privilege of interpreting (the academics and clergy) claimed to represent God exclusively. And that means power. And power uses ‘fear’ as a very effective weapon of crowd control.

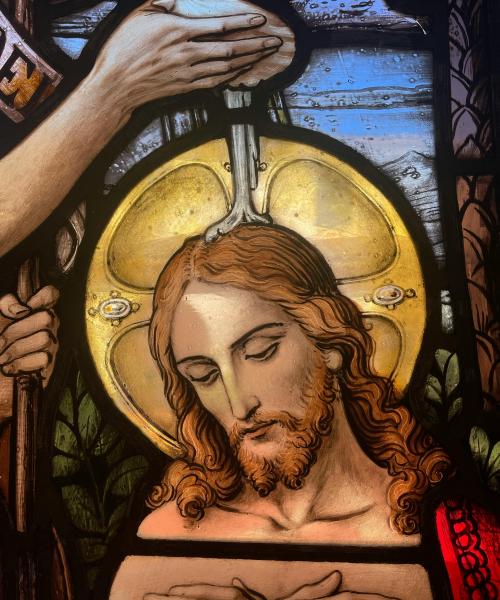

But Bartimaeus wasn’t invited to grovel in submission before the anointed one. Jesus did not describe God in ways that suggest God should be feared. And before you object, and suggest that the Old Testament gives us a rather grim picture of God, I’ll remind you that Jesus knew no other Scripture that what we call the Old Testament. Jesus represents the God he experienced, and that experience suggested awe and reverence – yireh – NOT fear, terror or great dread.

Think back through those snippets of Scripture that describe ‘the fear of the Lord’ as a good thing. And consider how we use that idea. Parents who (back in the day) would put the fear of God in you if behaviour wasn’t changed. That’s an exercise of power. Could ‘the fear/dread of God’ really be the ‘beginning of wisdom? Or is it possible that the awesome reverence of God would be the best start.

The Psalmist declares –“ O fear the Lord, you holy ones, for those who fear God have no want.” – but does terror solve anything? Is reverence for God the way to satisfy the longing we have?

The faith that Jesus rewards in Bartimaeus is not the faith of a trembling, terrified person. The crowd tries to quiet Bartimaeus becase fear of power means not speaking out of turn. Jesus steps right through that social convention – past that wrong-headed assumption about ‘the way things ought to be’ and asks to see him – talkes with him – shows compassion – rewards his ‘faith’ which was nothing more than a recognition that one who represented God so well – so completely, as Jesus did – would ceartainly listen to his request to be healed.

This is not the act of God who wants to make us afraid. It is the behaviour of God who deserves our reverence.

The saying goes that power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. We must acknowledge that in the Christian tradition, there have been too many times when these words we treasure have been given more power than the God who inspired them. The words which describe humanity’s collective experience with the Divine – the words that try to explain that Jesus lived, died and was raised – are human words and are ordered according to human understandings. But the power that inspires these words is incorruptible. The life, death and resurrection of Jesus are meant to drive out fear, in the way that love can (and does) set fears to rest.

“Come, O children, listen to me,” says the Psalmist; “I will teach you the fear of the Lord. Which of you desires life, and covets many days to enjoy good?”

The secret is coming in the next line, and it seems to me that terror has nothing to do with it.

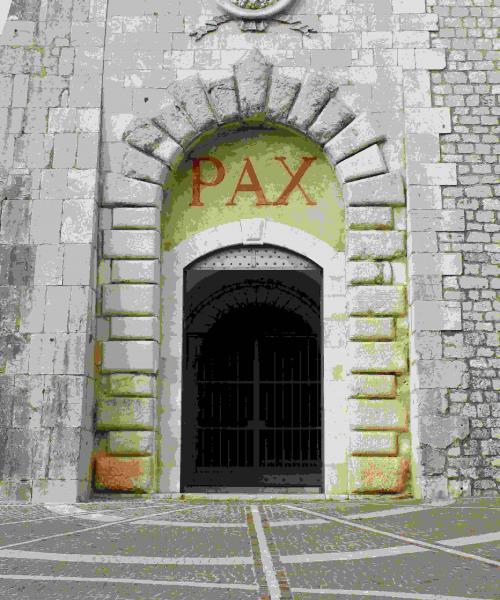

“Keep your tongue from evil, and your lips from speaking deceit. Depart from evil, and do good; seek peace, and pursue it.”

May ours be an attitude of awe and reverence – of doing good and seeking peace in the name of Jesus. For the sake of our Good God.

St. John's

St. John's