Sermon - May 05, 2019 Reality check

Reality check

There’s this thing that happens when you become a parent. From the moment you first lay eyes on your child - hold them - hear them - from the very instant you speak there name, you are living in a world of multiple realities. I’m not talking sci-fi, new star trek movie franchise kind of multiple reality - I mean you live (from that moment on) in a world of ‘anything goes’…

Sometimes, those multiple realities hold terror and dread - heartache and pain - but they also hold nearly limitless promise, and all at the same time. That is what makes the death of a child so difficult to bear. The loss of a young life is the loss of potential, and these losses diminish all of us. We know something of that here at St John’s. Even when the distances are great, we mourn those whose lives were too short - we ask questions of God and one another; How can this happen? Where is God’s sense of compassion? What sort of reality is it, where such things can happen?

It is an all too human problem, living with the knowledge that our individual (and collective) potential is at the same time nearly limitless AND perilously limited. Life is unpredictable - death is inevitable - and we must make our peace with that.

Not a new problem, of course - in fact, just the sort of problem that religions of all kinds have tried to help people deal with since…well the beginning of religion. Sacrifices to ‘appease’ the forces at work in the cosmos; temples and shrines to give focus to our anxiety; religious professionals to help us navigate the complex (and often fickle) demands of observance…these things are a feature in every kind of culture.

And slowly a way of thinking develops that dares to suggest there is this particular way to view the universe; one God, who manages the whole of our complex lives…

While it has become popular to dismiss religious influence in the 21st century - we’re a sophisticated species, after all; no need for ancient superstitions - the idea that there is a power in the universe greater than ourselves is still an urgent notion. Our questions need to be directed at something. Our grief needs a target, and our joy often prompts gratitude that has to go somewhere. Humans, for all our imagined liberty, are inherently religious. We can’t escape the feeling that there just might be an alternative reality - something better than we could create for ourselves; something wonderful and peaceful and separate from the confusing combination of emotions and reactions that make up our daily existence.

That is why we gather. That is why we worship. That is why we puzzle our way through ancient texts that recall a time when Divine reality was more easily imagined. That is the mystery of Scripture, after all. These are the words, thoughts and ideas of people who were wrestling with the evidence of God in the midst of their particular brand of human chaos.

These are the examples of the Patriarchs and prophets. The Psalmists and their wide variety of emotional expression(. ). Of Saul, whose understanding of how God engages the world was overturned in one shining instant. And then there’s Thomas.

The doubter, we call him - suspicious of the news that his ‘reality’ had been undone. He knew two things: Jesus had lived, and now Jesus was dead. The time before Jesus’ death was (for Thomas, and all the rest) a time of much promise. There was the hope of restoration and victory over the oppressive Roman regime. There was the hope of new days with new life - new structures to assure a new future - and in one horrifying moment, all of that was lost. Thomas knows how life works - he’s a realist - a pragmatist. He’ll treasure the good and learn to live with this new reality, limited and unlovely as it may be. That’s life, right?

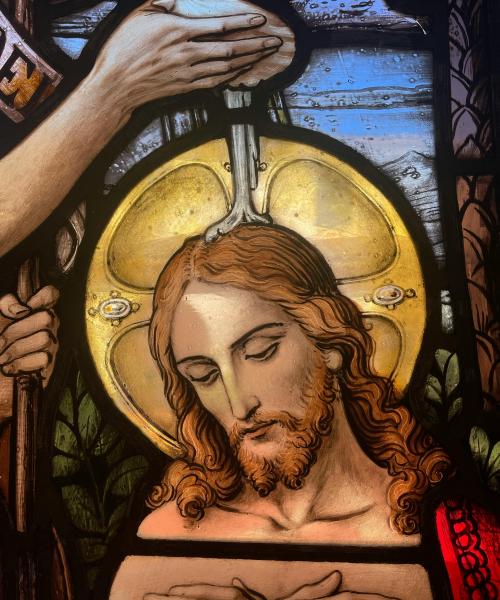

But the beauty of these texts - the mystery of faith - is that there is not a single reality at work here. Even at our most optimistic, our ideas have distinct limits. We are hampered by economy and environment - by attitude and of course our mortality. But what the children of Abraham took on faith we have been shown in the resurrection of Jesus. God who claims us is not limited by our understanding of time and space - life and death. The structures that we work so hard to prove and preserve cannot deflect the power of God.

So Saul discovered, while on his way to crush the hopes of those who dared believe in this divine reality. So too does Thomas learn that not even doubt spoken aloud can contain the power of the One who has promised to make all things new.

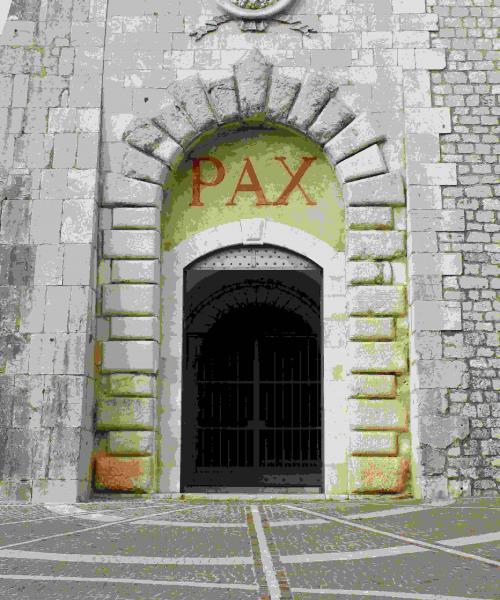

Our reality holds some hope and much disappointment - but we are not the masters of all things. Neither our certainty nor our doubt can erase God’s covenant of renewal and hope that finds its best expression in the risen Christ. Jesus opens the door to God’s reality, and teaches us to live in both places; in our disappointment and in our desire to see change. In our sorrow and our sacred hope; so that even in the shadow of death, we might recognize a new kind of life - open to all by the grace of God.

St. John's

St. John's