Sermon - Oct 03, 2021 Reconciliation

Reconciliation

So. Is it enough to love God? To pray fervently? To believe?

The church that grew out of the ministry of Jesus and the remarkable story of his persecution, crucifixion and resurrection, is built on the premise that belief, prayer, and love (in that order) are sufficient to free you from the perils of an otherwise unexamined life. Parables and second-generation stories of miracles help to draw us into the premise that salvation – reconciliation with God – life abundant – are all available according to some sort of formula.

You know what I mean. We are, as people of faith, products of church practices that include early training in the stories of Scripture – all of which are meant to show us what God is like, and why Jesus is worth following. Catechisms, memorizing Scripture, acting out our favourite stories – none of these things are bad at all – most of them are excellent, in that they ignite our curiosity and give us a hunger to know more about God, the universe, and our place in it.

But, being trained in this system of salvation – having been convinced that Jesus is the answer, no matter what the question – cannot keep you from those experiences that call your belief into question.

Job handles it one way. The person we meet in Mark’s gospel offers a different, and more familiar refrain.

Job is often held up as the model for how to respond when bad things happen to good people. As a person who found favour with God, bruised and battered by the fickle nature of life, Job chooses to ‘stay the course.’ “God gives and God takes away – blessed be the name of the Lord, -- so Job famously says after hearing that his children are dead and his worldly goods destroyed.

His attitude doesn’t change much when his personal health is affected; “shall we receive good at the hand of God, and not receive the bad?” Good old Job – Job the rock; but not, as it happens, a hopeful model for those who would pursue faithful living.

In the end, Job is reconciled to God…kind of. Job acknowledges that God’s ways are unknowable – Job takes his lesson in stride (and why not? His fortunes are soon restored – an early example of an author opting for the ‘happily ever after,’ cop out ending) but Job’s example does not offer much guidance toward reconciliation with God beyond accepting whatever comes, and enduring - with painful stoicism - the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.

Not an attractive option.

No, our engagement is a little more active – a little more frantic…more like the father who we find at the centre of a controversy in Mark chapter 9.

Jesus, returning from a brief retreat with Peter, James and John (Mark 9:2-13 – Transfiguration) encounters a crowd who are engaged in a spirited debate. Scribes and citizens alike, a babel of noise and emotion, and one voice offers the summary for Jesus’ sake: ‘Help! My son is in distress. I brought him to YOUR disciples to be liberated, but they could not do it...please sir, if you are able…’

Jesus goes on a short riff on faithlessness, and proceeds to heal the boy (and astound those who are watching) – but not before that famous exchange. “All things can be done for the one who believes.” And this person responds with the all too human combination of faith and frustration; “I Believe; help my UNBELIEF!”

Like this nameless character from Mark’s gospel, we tell ourselves that belief is not the problem. We are (as I mentioned earlier) products of a system of belief that stretches back over centuries; traditions and Scriptures and Sunday School lessons full of meaning, all of which promised ‘the faithful’ some sort of comfort, or satisfaction. And far more often than we’d like to admit, we are not comforted – not satisfied – and the promised security of ‘personal salvation’ seems very empty indeed. What’s going on?

Our belief is surely not in vain, is it? We have found comfort and joy in the company of the faithful – we have found relief for our fears through prayer and in Scripture. Faith is not void, nor do we hope in vain (to paraphrase Paul) but ther is so much that doesn’t seem right – so many questions – so much misery ad brokenness around us. And what’s worse, some of that misery has its roots in our faith communities; in residential schools and in other places where the rampant abuse of power has been allowed to fester and wreak havoc among the faithful. How do we reconcile these things?

For reconciliation is much on our minds these days – mostly as a reminder of how badly reconciliation is needed – but what does it look like? How can it happen. Our modern version of the prayer from Mark 9:23 might well be “Lord, we desire to be reconciled; help us bridge the gap between desire and action.”

What Jesus does in today’s gospel lesson (Mark 9:14-29) is first call the affected person into the midst of the crowd. “Bring him to me.” By doing this, Jesus makes room for this person’s brokenness – the circle of humanity must get bigger (in that place) to make room for his unpredictability when the spirit takes hold of him. And when his wounds are acknowledged – when space is made for his brokenness – acceptance and healing rushed in to displace the spirit of brokenness. A miracle.

Acknowledgement of this wounded person was required before healing could take place. Stories – horrible stories – must be heard and acknowledged; story-tellers bring their grief and their mourning to the table, and that requires all of us to shift a little – to make room for the baggage they carry. And little by little, the space lets us share the burden of hurt, and the healing proceeds…little by little. Still a miracle.

Whether those wounds manifest as hereditary trauma, or addiction, or anger, or fear, or mental illness, or homelessness, or bitterness, or all of the above, Jesus would have us make room for those wounds in one another – Jesus invites us to make room for the broken parts of our lives, so they can be recognized and named, and begin to heal.

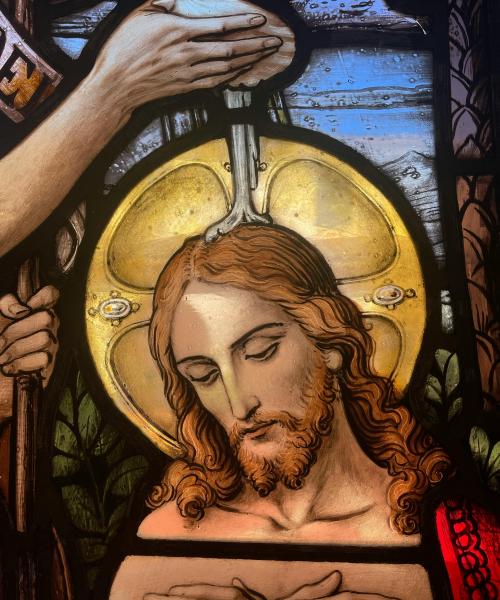

This is what we try to do when we pray – weekly – for forgiveness. This is why we acknowledge our brokenness when we gather around the sacraments, for at the font and here at the table, Jesus makes room for everyone and anyone. In the bread and wine, Jesus reminds us that there are empty places in each of us that God would help us name and acknowledge so they might be filled (eventually) by grace and peace.

Come, take and eat. Come and be recognized for who you really are. Be fed, and maybe even liberated by a Sacrament that makes room for everyone, wounds, warts and all.

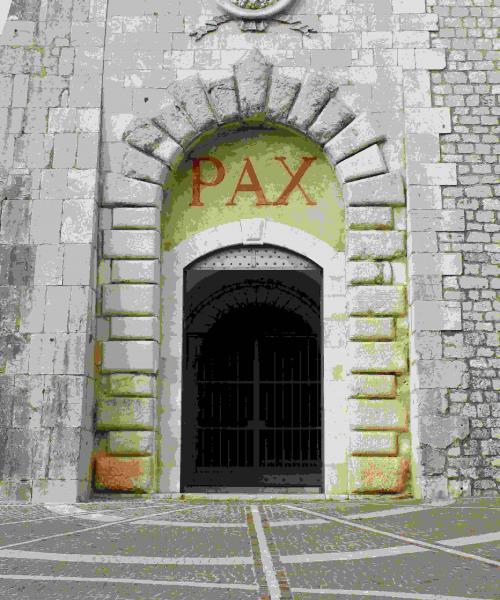

St. John's

St. John's