Sermon - Feb 25, 2024 Take up your cross

Take up your cross

Now, everybody loves a good origin story. We fuss over our family tree – we delight in finding connections to cultures and times that are all but forgotten in our day-to-day living. Such explorations make us feel connected – maybe even a little bit exotic. But this origin story is not like that.

Abraham is described as the father of all God’s people. And it is remarkable - given all there is to choose from – that God has looked down and said: the real connection starts HERE. With a childless couple who are (in that moment) strangers in a strange land.

Let’s not think about it as God playing favourites – though that is often the assumption. Let’s consider instead that our ancestors in the faith used this story to describe an evolution in their relationship with God.

Let’s consider that Abraham, with his new name and the promise of children to sustain him, was the first to credit God – the first to claim God’s blessing - the first to try and imagine what a life in God’s company might look like.

God ‘speaks’ and Abram falls to the ground in wonder. New names are offered, and a new future is described. And then, the work begins.

We have heard enough of Abraham’s story to know that it’s not all sunshine and daisies. There comes a time when the promised children cause problems in the household. Abraham – God’s favourite – is forced (by Sarah) to choose between his children. The covenant is one thing “I will be your God…” Living into that new reality is another thing altogether

The new reality – this covenant of ‘walk with me and I will be your God’ begins, almost immediately to be modified. Ishmael (Abrham’s son by Hagar) will be successful, but the children promised to Abraham & Sarah will be something else altogether. To avoid these challenges, the story follows Issac and excludes Ishmael (the son Abram already has.) The authors identify the problem, and propose an explanation. It’s a harsh solution. Living into a covenant is difficult. It always has been. Humans make all kinds of accommodation. Scripture – whatever else it is – also describes the history of our adapting – trying to live into these ancient promises.

That history brings us heroes and villains; prophets and judges; poets, priests and kings. And in God’s good time, we meet Jesus in the story.

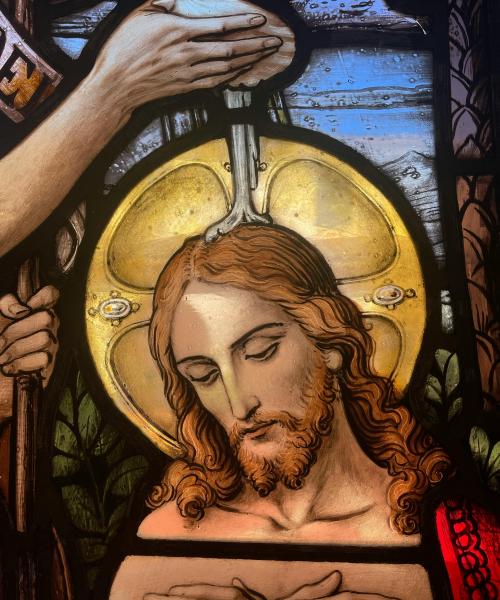

Jesus comes proclaiming a promise that God’s ‘kingdom’ has come near. His words and his actions suggest the promises that people have long struggled with shall soon be better understood. Jesus declares (and demonstrates!) that God is active in the world, working for justice and moving in compassion and grace.

This is the Abrahamic promise, only livelier.

God is no longer just waiting patiently for people to “walk before me and be blameless…” God is in the midst of us.

Active. Present. Engaged in ways that the ancients could only dream about.

And Jesus turns the promise around.

Abraham is invited to walk before God and be blameless.

Jesus says “take up your cross and follow…”

We are happy to put our shoulders to the wheel or our noses to the grindstone. We know that work is expected, and that some of it will be hard. But a cross? Death of self – loss of life – most of us get cold feet at this point, and would rather such desperate choices not be offered us…especially by our beloved prince of peace.

Make no mistake. People have lost their lives in the service of the gospel. Choosing ‘team Jesus’ can lead to some challenging interactions. But the good news proclaimed by Jesus – the covenant into which we are invited to live – is a covenant of life abundant. And so, this call to take up an obvious instrument of death is problematic. We need to explore – to make accommodations. Not because we would dilute the promise of God, but because the promise of God is not meant to diminish us.

Jesus dares us to dismiss our old certainties. To put to death the things which once defined us. And for the church – the ideological children of Abraham & Sarah; the self-proclaimed family favourites – that just might mean putting to death the notions and doctrines that present us as ‘better than’ those who exist outside the family. Jesus flaunted the rules of ritual cleanliness – blessed those who did not - in the eyes of the law - measure up.

Rather than a set of rules to bind us to one another, Jesus demonstrated the behaviour that heals. Jesus understood that God’s covenant is made known through active and intentional relationships.

The act of loving neighbours and enemies alike – especially the connections that we make beyond the reach of our religious certainties – help us to understand the fullness of who (and what) God may be. Suddenly, instead of a small but fiercely devoted group calling itself ‘God’s people,’ we see that God has a large, diverse human family, whose only point of connection is that they are loved by God.

So it is that in the final week of his life – knowing that the system of certainty was preparing to have him arrested and killed – Jesus gathered his friends together. None of them perfect. One of them a traitor. All of them sure that they knew how God should act. He gathered them together, blessed them for the struggle by sharing the Passover meal, then left them to puzzle out what happened next.

The church developed from that group of 12. One, so distraught at his misunderstanding, would commit suicide. The others would spend their lives trying to figure out the mystery of a risen teacher and a legacy of love that would change their lives - and change the world. That mystery is ours to share – and Jesus’ invitation is our biggest challenge: to put aside our drive to ‘get it right’ and instead to take a sacred risk. To love the unlovable. To expand our imaginations where God is concerned. To see beyond the limits of our fears, that we might live into God’s covenant of grace.

St. John's

St. John's