Sermon - Feb 18, 2024 The Kingdom of God has come near

The Kingdom of God has come near

We start with a fresh start.

The flood waters have abated – the ark sits on dry ground. Noah and his sons (so the story goes) are granted an audience with the almighty. It’s a great and terrible story. We share it with our kids. We wonder about the state of hygiene aboard that floating menagerie. We turn it into a nursery story…but it is not.

What if this is a cautionary tale about the kingdom of God. You remember the kingdom of God? The thing that Jesus spends so much time telling us about? The thing we sing and pray and long for?

The thing we’re not sure how to define.

Noah ‘gets a warning’…and builds a floating shelter. In that ugly, smelly barge (so the story goes) Noah, his immediate family, and a problematic collection of animals are saved from destruction. So far, so good.

But this is a carefully crafted piece of religious mythology. Yes, there have been historical floods. And yes, people who survive these events often credit divine intervention. Calling Noah’s story (or anything else, for that matter) religious mythology does not rob the story of its power. This is a very powerful statement about how mere humans might engage with the Almighty. Noah’s story contains necessary life-lessons for any who would profess faith in God.

Going in, God can (and does) do anything. Sees all – knows all…and seems to approve of nothing EXCEPT WHERE NOAH IS CONCERNED. Remember the way the story starts: (Genesis 6:5-8)

The Lord saw that the wickedness of humankind was great in the earth, and that every inclination of the thoughts of their hearts was only evil continually.

And the Lord was sorry that he had made humankind on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart. So, the Lord said, ‘I will blot out from the earth the human beings I have created—people together with animals and creeping things and birds of the air, for I am sorry that I have made them.’ But Noah found favour in the sight of the Lord.

This is how the author sets the scene. This is the state of human relations with the Divine at some far-off point in our history. And it is about to change.

Sure, the manner of the change is described as horribly violent and needlessly destructive: major social change is often both of those things (unfortunately.)

But once the dust – or in this case, the water – settles, the author reveals that God has set new rules of engagement.

We get hung up on the violent nature of God’s activity in the Old Testament. We shouldn’t. What we read and describe as God’s violence is most often human activity using God as an excuse to act violently. Natural disasters and other inexplicable things are ‘blamed on God’ (as they are still) but God is not intrinsically violent. Where the Bible offers “God’s words or thoughts, such offerings must always be imaginatively interpreted. God doesn’t offer one-on-one interviews. God is experienced through other means.

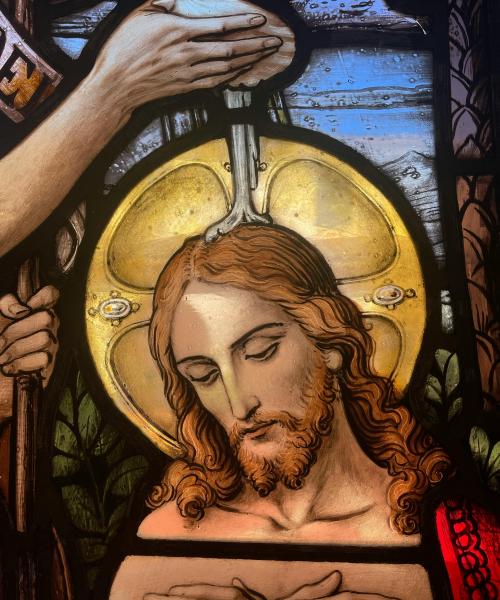

Which brings us to Mark’s gospel – and Jesus: baptized, tempted and suddenly in the spotlight (since John has been arrested…) Jesus, who – in Mark’s gospel, at least – seems to appear out of nowhere. And it seems in that sudden appearance of this mysterious, holy man, we will find a new way to experience the Divine.

Jesus is introduced (in Mark’s gospel – and in the context of all of Scripture) in the middle of the story. Humanity still has all the usual problems: war, occupation, hunger, inequity. There are powerful people lording it over those who might just be powerless. And out of the desert, into our story, walks Jesus – the beloved.

Unlike the Noah story, the Gospels describe a different kind of engagement by God. Here in Roman occupied Palestine, when the world has failed to live up to ‘God’s expectations’ – God sends a representative.

Sure, there have been prophets and priests and kings, but that sort of overt power has always been problematic in human hands.

So instead of an authority figure – someone to run the temple or rule the nation – God sends a teacher.

The covenant with Noah was God’s promise to be aware; a promise to give the world a chance. A promise to contain God’s awesome power. That promise (still in effect) allowed the history of the Hebrew people to play out from success to failure to success again. But that cycle of history, while it brought the people an awareness of God, didn’t bring God any closer. And the kingdom of God remained a distant, mysterious promise.

In Jesus, dusty from his desert sojourn and standing in for his mentor John the Baptist, God offers the promise of engagement (rather than detachment.) No more ‘God as a distant overseer’ – Jesus declares God to be in the midst of us.

The kingdom has come near. Not to threaten or cajole. Not in an act of retribution, but in hope of reconciliation.

++++++++

There are church people. Good, solid Christian folk – who will declare that we won’t see God’s delight until the world has either been torn down, or we have torn it down. There are lovely, faithful people whose image of God is still that of the ‘flood-director;’ waiting for the next chance to wipe the slate clean…except for the particularly faithful.

These are people we often know…and love. This kind of talk is hard to hear, but easy to believe in our current circumstances. The world is a disappointing and often terrifying place. God’s kingdom would certainly be better.

And it would be easier to think that, one of these days (as the story goes) Jesus will return and God will (once again) clean house and start over.

But Jesus suggests something else. Jesus brings the kingdom. Jesus points out the nearness of it; invites us to look for it, work for it…to revel in the joy of it. Not in some far-off time of Divine reconstruction, but in our own time.

The act of reconciliation happens in the midst of disaster. The power of love and compassion – mercy and grace – is most notable when the world is at its worst. Our call to love both our enemies and our neighbours is a call to glorious defiance. The ‘powers that be’ depend on our sense of discouragement. The suffering world doesn’t need God to wipe out the wicked. What is needed is for Jesus’ followers to live out the kingdom.

The stories of our faith – stories that remind us of our part in the drama – still need imaginative interpretation. That is the task of faithfulness. We won’t always get it right, but we can choose between the simple “God will take care of it” approach of those who imagine another ground-clearing act of God is our last, best hope and the ‘God’s kingdom has come near’ challenge that Jesus offers us.

The former requires only that we try to stay on the side of perfection. The latter calls us to action in pursuit of Jesus. In this world gone mad that we call home, which will you choose?

St. John's

St. John's