Sermon - Oct 22, 2023 Whose side.

Whose side.

It’s in our nature to pick sides. It’s a protective instinct – a reflex that helps (surround) us with something like safety and assurance. It goes without saying that our side doesn’t always prevail. Even in our most ancient stories, there are ‘winners and losers.’ The titans are banished by the Olympians. The city of Troy is overwhelmed by the Greeks. Israel is dragged into captivity by historically powerful neighbours

In these stories – when the ‘good guys’ hit a rough patch – we know how the story should end. Somewhere among the momentarily defeated ‘good guys,’ a hero will emerge – someone who helps the downcast find a way. Someone who throws off the chains of slavery and rises up to teach the ‘other side’ a lesson. That’s how we like our stories; full of tension and drama, with a solid, predictable plot that leads us to the hero.

But OUR story doesn’t follow that path. Isaiah is intended for a nation who are on what seems like an endless exile. They are, in fact, practically embedded in a foreign culture. God’s promise of deliverance still holds, but it’s hard to imagine what that deliverance will look like. Generations have gone by. Cultural identity is in danger of being lost. Maybe God has forgotten them after all…

God sends a hero to the Israelites. Cyrus. The king of Persia.

The deliverer is a foreign ruler. An outsider. One whose history would not suggest sympathy with the cause of God’s people. But Cyrus understands justice and compassion. Cyrus is described as “God’s anointed” - a precious title in Scripture – and becomes an instrument of God’s own presence. Not unprecedented, but unusual. There is something going on here that should inform our habit of choosing sides.

The history of God’s people is full of upset and uncertainty. Prophets come and go – the people are constantly reminded of the promise of God, but generation follows generation with no clear sign of relief. The conquering nations blur into one another until it’s the Romans in the driving seat. The religious habit of remembering the promise is still maintained, but those in charge of the remembering are playing a dangerous double game. Power in a seductive mistress. Those who have responsibility for the conduct of public devotion are constantly choosing between the favour of the Romans and their duty before God. Accommodations are made – compromises are on offer. Cultural identity is hard to maintain. The promise of God still holds, but it is tempered by the reality of Roman rule. And into the midst of all this comes Jesus of Nazareth.

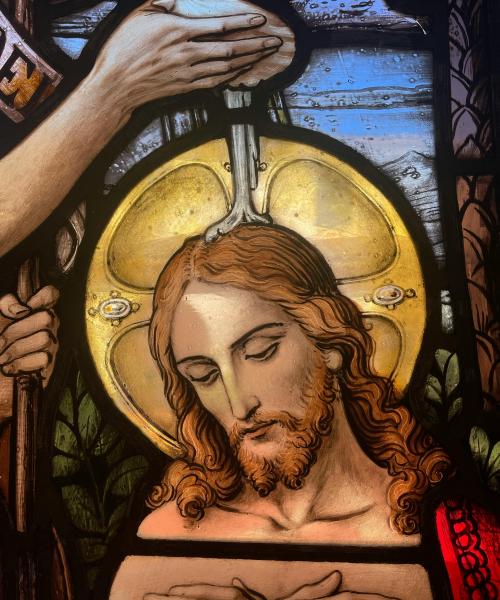

Forget – if you can – the stories we tell of his wondrous birth. Mark’s gospel skips right past those. This gospel describes the emergence of a man whose baptism was marked by voices from heaven. For the author of Mark’s gospel, it’s Jesus’ association with John the Baptist that matters. One outsider blesses another as the story begins.

Jesus has made a splash in the countryside. Healing and teaching and offering alternatives to the tired narrative of ‘God will restore our glory.’ Jesus offers God’s glory as a touchstone. Jesus would redeem the religious narrative, and humanity along with it.

By the time Jesus gets to Jerusalem, the people are listening – and the professional religious establishment is worried. The people imagine that Jesus is the hero in the traditional sense. One rising up from the rabble to lead the oppressed to a stunning victory. The Romans will be put in their place and the people of God will be rewarded with power and prestige. Jesus is all their hopes come true. Local boy rises to prominence.

Forget the stories we tell about his birth – pay attention to the tension in the air as he mounts the temple steps. This is where it will begin. This will be their moment…

And in that place of sacred promise, Jesus blows their minds. He rails against the established religious order. He flips tables and chases merchants from their stalls. The revolution seems to have begun, and in the strangest place.

The first thing to go will be their iron-clad religious certainty. Patterns and practices that have been taken for granted; habits and time-honoured traditions that serve no sacred purpose; these things must be thrown down. The people are spellbound. The professional religious folk are terrified and angry. They understand that their power and privilege are at stake. There will be a reckoning.

And for a while, in the aftermath of Jesus crucifixion and resurrection, the lesson that he taught was taken to heart. The folks who followed Jesus – the faithful who proclaimed a different way to understand God’s promise; a new way to recognize God’s revelation – those folks wandered and taught and encouraged and sometimes died for their convictions. But the powerful know a good thing when they see it.

Religious rules and promises have always been an effective way to control large groups of people. Once Christianity became the religion of the empire, the tone of devotion changes. Monuments are built, which must be maintained. Institutions are established, which must be obeyed.

In the History of Christianity, every 500 years or so, there is a reckoning – a reformation – as some in the church call the faithful to examine priorities and consider the reality of ‘God-with-us.’ We may well be working through one of those historical moments.

The chaos in society – regions savaged by war and a planet groaning under the weight of our indifference – all of this has some people (especially faithful people) asking if this is the moment. Are we poised for a hero to show us the way – to redeem all things and restore the glory of some misunderstood past?

The truth is, we have already been given such a hero – and Jesus didn’t act as we expect our heroes to act. He overtured sacred habits. He invited us to question the long-standing traditions of the church. He dared to suggest that it was possible to have a relationship with the divine – that God was interested in the here-and-now.

Jesus talked in ways that made the fervently faithful very nervous – so nervous that they arranged his death with the Roman authorities. What do you think Jesus would say to us? As we wonder aloud ‘who will save us?’ What would Jesus say as we scurry to choose sides in the so-called culture wars? Whose ‘side’ do you think Jesus is on these days?

I dare say we’d all be surprised by the answer.

St. John's

St. John's