Sermon - May 21, 2023 Either, or...or maybe both

Either, or...or maybe both

Sin or grace? Solid foundation, or shifting sand? On the face of it, the choice seems obvious. But we have a talent for complicating things. For example – every time I see (or hear) the word ‘therefore’ in one of Paul’s letters (only twice in this morning’s lesson) I hear myself saying (or thinking) ‘yes, but…’:

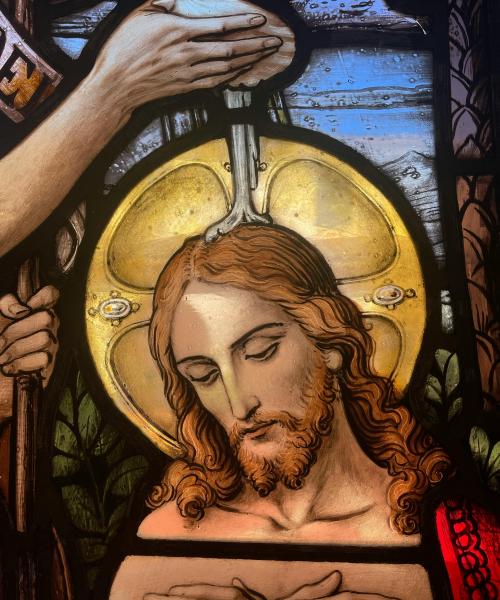

Yes, but our burial by baptism is a strange metaphor (and we have a hard time using death as a positive sounding experience). Yes, but simply choosing not to let ‘sin exercise dominion in your mortal bodies’ requires more than a little willpower…Paul is making an elegant point here, but we are easily lost in its elegance, and part of the problem the word ‘sin.’

There is a great burden of meaning and influence attached to this tiny, English word. Sin is everything that is wrong with humanity. Sin is everything we envy and despise in another person. Sin has become the thing we fear, the thing we don’t understand, the thing that holds our curiosity, the driver for legal, political, and social action. And most everyone defines sin differently.

And for all that we’ve tried to paint a picture of what it is Paul wants us to avoid, (there are, in some letters, helpful lists of illicit behaviours), the best definition of sin that I know of is that sin is the act of separating or distancing ourselves from God. Over and over, this little English word stands in for a Greek word that indicates something is missing – hamartia.

How does it change your thinking if it turns out that sin isn’t a particular thing – an activity, a behaviour, and instead, is understood as the absence of a thing – compassion, empathy, love, or grace?

There is a contest in the world – it plays itself out in elections most vividly. Two sides line up to win our affections. They seek the right to chart our collective course for a time. Each side has some experience in the job. Both sides have intelligent, capable people who feel called to this grand project. And the argument being made is always reduced to the wickedness or unsuitability of the other side. You can discover, if you dig deeply, the principles that guide each party. Their platforms are public documents (if you don’t mind a little literary archeology). But the practice in an election campaign is that each spends as much time as possible replaying the sins of the other. That’s because ‘sin’ is sexy. Sin provokes an emotional response. The assumption is that sin is well understood, and clearly defined, and universally reviled. Nothing could be further from the truth.

When the strategy calls for the constant belittling and undermining of the opponent, then all that the winners have in common is a distaste for the opponent; their ideas, their actions; their humanity. The constant desire to see the opponent as flawed creates its own sin. And what is absent most often is understanding. Compassion. Respect.

And before you get feeling smug about how awful politicians are (they’re not) I’ll remind you that the church has perfected this manner of division down the years.

“Hate the sin and love the sinner.” Do you remember when that was the battle cry? It’s been used in various circumstances, but usually directed at LGBTQ folks – occasionally at addicts, or homeless, or otherwise differently privileged people. All this because we turned sin into the presence of something we didn’t like.

Paul’s complicated argument against sin is an argument for grace – he just makes it from the wrong direction. When we turn our backs on grace – on compassion – on love – on God – then we create the absence that Paul calls sin. And Jesus offers us an alternative way to live. He encounters those who are different – outcast because of their behaviour or their afflictions – and offers compassion and understanding. Jesus treats the leper and the foreigner - the women and the outcast – as children of God, rather than miserable sinners. And the result is that their lives are transformed. They walk – they worship – they praise the god who made them.

Sin is certainly a problem. And the solution is a return to God. But the thing we must leave behind when we turn to God and face the truth about our behaviour is our unfortunate habit of turning people into sinners because we don’t like who they are, or how they worship, or how they have to live.

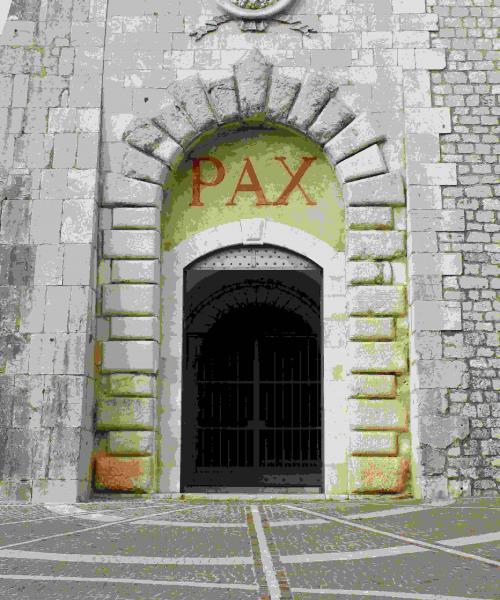

Jesus greeted the outcast and stranger as children of God – part of the family. He saved his heaviest criticism for those who manipulated religious rules to their own advantage. One is rock, the other, sand. And you know what happens to those who build on sand.

St. John's

St. John's