Sermon - Nov 06, 2022 Whose authority

Whose authority

We may wish it to be otherwise, but authority matters. Governments need authority to govern; leaders, to lead; teacher, preachers, employers, coaches - everyone of these requires the consent of those who are governed, lead, taught, employed or coached. Without authority, chaos isn’t far away.

Authority helps us ‘order’ things - we can make sense when we know who’s in charge, and we respond based on how that authority is exercised.

Abuse of authority, while effective for some, is generally not tolerated for long. These are lessons that history and sociology have long been willing to teach us - and there are always those who want to exploit the notion of authority for their own advantage.

On this day, there are the proverbial posse of priests and scribes who are eager to discover what side of the game Jesus is playing. Their question - not surprising - is of authority.

Jesus’ influence is growing - he might soon become his own ‘authority;’ and the gospel by this point is clear on what the religious folks prefer; They want Jesus dead.

Their challenge is meant to go right to (what they imagine is) the heart of the matter; Who’s your boss? Who (or what) gives you the right to do and say the things you’ve been doing and saying?

We might wonder why it matters? Free speech and a multiplicity of public opinions have spoiled us. There are times - and places - where acting as Jesus did is a very real threat to those in power. Jesus words and deeds expose injustice - Jesus presumes (over and over again) that people are better than their current behaviour - that they ought to act differently; in ways that honour the general goodness of their created-ness…

Jesus proposes a new way of looking at life and order and authority - and this new way makes the authority of the day very nervous (it still does…)

So who do you think you are, Jesus? Where does this come from?

And Jesus, when faced with questions like this, asks a question of his own.

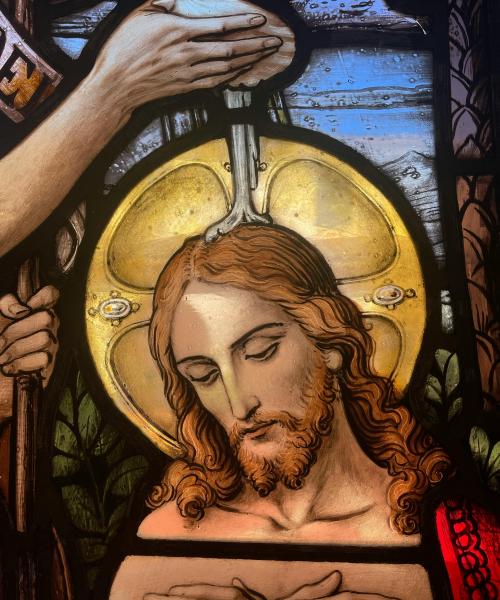

A question about ‘the baptism of John’ exposes the motives of those who wanted to put a stop to Jesus’ work. Luke goes further – stating that they were looking for a way to kill him – but then Luke knows how the story will end.

Jesus puts the work of John in front of his questioners, and now they have a problem. Jesus gives them two choices – John’s baptism was either from God, or it was a human notion. The scribes can’t imagine that there might be another answer – a more complex, more nuanced answer – so they don’t answer at all. Jesus returns the favour and won’t answer their question – not just because the answer should be obvious, but because the answer is also complicated.

Jesus lived into that complexity: full of the grace and mercy of God, and fully human, he is the best example of how to manage the many claims of authority we find on our lives. ‘Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s – and to God what is God’s’ he famously says elsewhere – acknowledging that we must engage the complexity of this world. Jesus showed us something else though – the complexity makes sense if you put God first.

Putting God first among the many authority figures doesn’t mean we pick and choose whom we obey according our convenience or comfort – no, using God as the measure of graceful, compassionate disciple; the highest example of loving-kindness helps us know when to accept and when (and how) to challenge those who have authority over us.

There are those who imagine that ‘following Jesus’ in this way means measuring every authority against the perfect mystery of God – which means, of course, that none on earth deserve our obedience. This is an unfortunate oversimplification. Jesus understood the fallen nature of our human systems, and his challenges were meant to transform those systems, not ignore them.

Jesus calls us to engage with the authorities and through our engagement, to help transform the broken, mindless, care-less systems – systems that we cannot do without.

So, following Jesus’ example, governments aren’t to be despised, but questioned, challenged, and called to higher standards of care for those whom they govern. And the same holds true for employers, law-enforcement, educators, coaches, parents…the list goes on. Any who expect loyalty and obedience should be held to a standard of behaviour that puts priority on justice, mercy, compassion and care.

It's not simple at all – the answer is not either-or. Jesus’ question stumps the powerful, whose authority is limited by their failure of imagination. The reign of God is not like the empire of Rome – not like any human government or institution. The authority of God is shared responsibility. To honour the Creator, we are called to care for all creation. To love God requires us to love one another – and the act of caring and loving brings to life a different approach to authority.

Living for and longing for this approach to authority will still ruffle some feathers – it will still bring us frustration about the state of the world. Following Jesus example where authority is concerned is no guarantee of a comfortable, trouble-free life. But it is a life of clear conscience – a life of great reward.

It is a life lived in faith, which is all that Jesus asks of us.

St. John's

St. John's